RANSAC for finding a plane

This post shows an implementation of Dynamic Sampling RAndom SAmpling Consensus (RANSAC) that finds the largest plane in a default pointCloud from Open3D.

This post will discuss how dynamic sampling for RANSAC works from a conceptual perspective, as well as how it applies here. With the conceptual guide, you should understand the approach well enough to use it in outlier rejection of all sorts.

Operating

Clone and run my repository

Principles of RANSAC

In general, when trying to find outliers in a dataset, it can prove to be very time consuming. In general, you expect to test all the points and see which ones produce the best hypothesis for the data. This is a way worse approach than \(O(n^2)\). Is there a better way? Well evidently.

Dynamic Sampling RANSAC uses three key insights each iteration to create an extremely efficient and lightweight solution to outlier rejection that is used accross many industries today, especially perception and computer vision.

Insight One: Minimum Hypothesis

For each iteration of this approach, we need a hypothesis. For RANSAC, we choose the minimum number of datapoints that can create this hypothesis for us. In the case of estimating a plane, that requires three points. If you were estimating a homography, you would need four. If you were estimating the F-matrix between two camera perspectives, you would pick seven.

Using this hypothesis, you can estimate the number of points that fall within a threshold of the hypothesis, and generate an estimate of how accurate the hypothesis may be. If you capture a large number of data points as “inliers” with the given hypothesis, that means it is a good guess.

Because you are doing a minimal hypothesis, you can choose many different hypothesises over the dataset to try to find the best one

Insight Two: Probabalistic analysis of outliers

Assuming a global solution, if we were to pick all inliers for our hypothesis generation, we can assume that the generated hypothesis would describe the global optimal hypothesis pretty well. Therefore we can call the probability we pick an inlier \(P\). We call the ratio of \(\frac{inlier}{outlier}\) as \(\epsilon\).

We know that the probabily \(P\) can be defined as

\[P = (1-\epsilon)\]If we need to pick \(s\) number of inliers for our good hypothesis, we can say that the probability (with replacement for simplicity) this occurs is:

\[P^s = (1-\epsilon)^s\]Insight Three: Stop when you are done

In general, we repeat the process for selecting points, generating a hypothesis, and determing the number of inliers \(N\) times. After \(N\) iterations, we simply retain the hypothesis with the best number of inliers as our estimating best global hypothesis. But how do we find out an \(N\) that ensures we found a guess that is good enough?

Solving this problem requires another probabalistic analysis of the issue. Since we know the odds that we pick a “good” hypothesis is \((1-\epsilon)^s\), we can know that the odds we pick a “good” hypothesis over \(N\) trials, written as \(p\) is

\[p = 1-[1-(1-\epsilon)^s]^N\]We can solve for \(N\) simply:

\[N = \frac{\ln{1-p}}{\ln{1-(1-\epsilon}^s)}\]If we wanted to have a 99% probability of solving for a “good” hypothesis, we simply need to plug in our known \(p,s\) and tune our \(\epsilon\) for our data.

Dynamic Sampling

Dynamic sampling takes this one step further by enabling the loop to exit when you have found a solution that is “good enough”, which in practice is the way you will see RANSAC used.

Ya see, it turns out instead of tuning \(\epsilon\) to be good for your data, you can instead use the ratio of outliers to total data given by each hypothesis at each time step. The algorithm looks like this:

N = ∞, sample_count = 0

while N > sample_count

form hypothesis and check inliers

Use new outlier to calculate ε

use new ε to calculate N

increment sample_count

This may seem a bit confusing. Lets look at the three cases that can occurr to get a better understanding of why this is such a smart approach.

First, the algorithm may pick a great hypothesis. If you pick a great hypothesis, you get a lot of inliers and a small number of outliers. In this case, you expect N to be very small, as the data has a large number of inliers and therefore a large chance to pick a great choice. If you calculate an N that is smaller than your current count, you can rightly assume that you have already picked a hypothesis with the accuracy threshhold you have already accepted, so you can exit.

Second, the algorithm can pick an asbolutely terrible hypothesis. In this case, you get a large outlier count, and a large N to boot. Now this can occur early in the algorithm, and you just simply continue as normal, or you can pick this later on in your iteration count. Either way, the previous logic applies: if you have terrible data with many outliers, you are deep into your iteration count, and your N is smaller than your sample_count, you can rightly assume that you have already found the best hypothesis you can find. Furthermore, if N is greater than sample_count, you can still hold out hope you will pick the a great hypothesis and exit soon.

Third, the algorithm picks an average hypothesis. In this case, you expect a medium N. The logic from the above two cases still apply. If your sample_count is higher than your medium N, you can still safely exit. If its smaller, you can still hold out hope for a better guess down the line.

The core insight here is that great guesses with low outliers SHOULD cause your algorithm to exit, as by forming that hypothesis, you gain insight into the true \(\epsilon\) of the dataset.

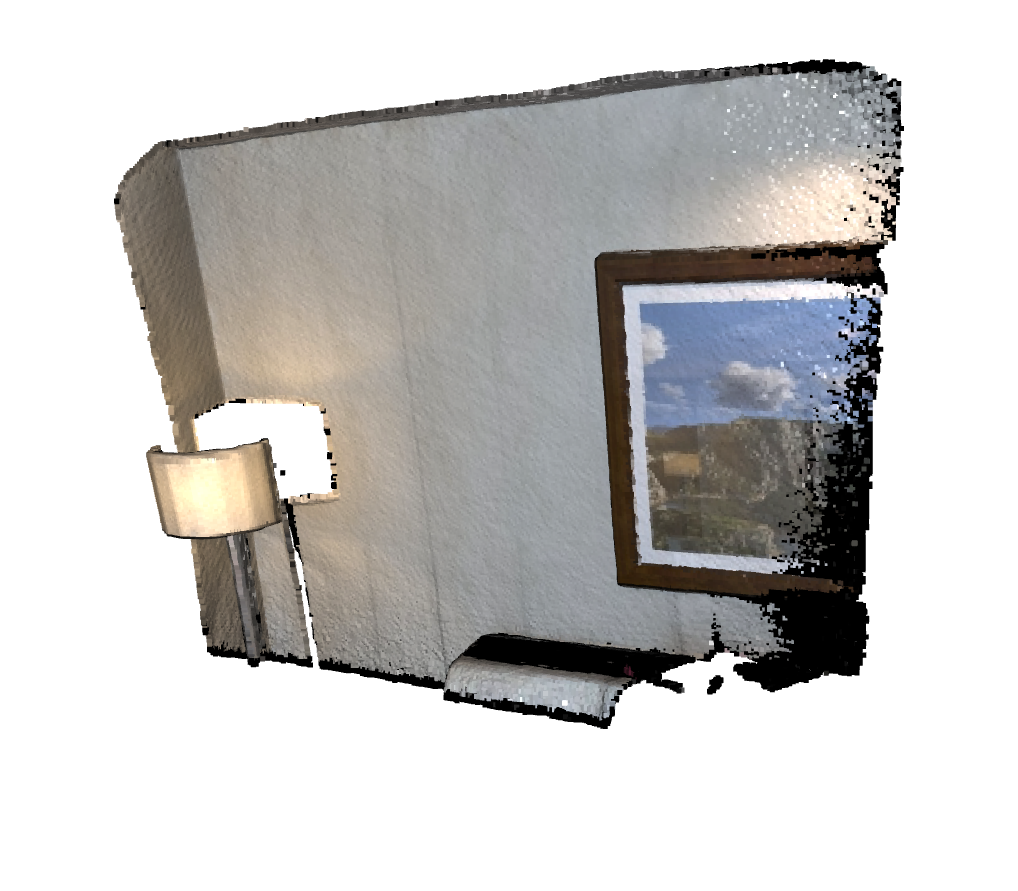

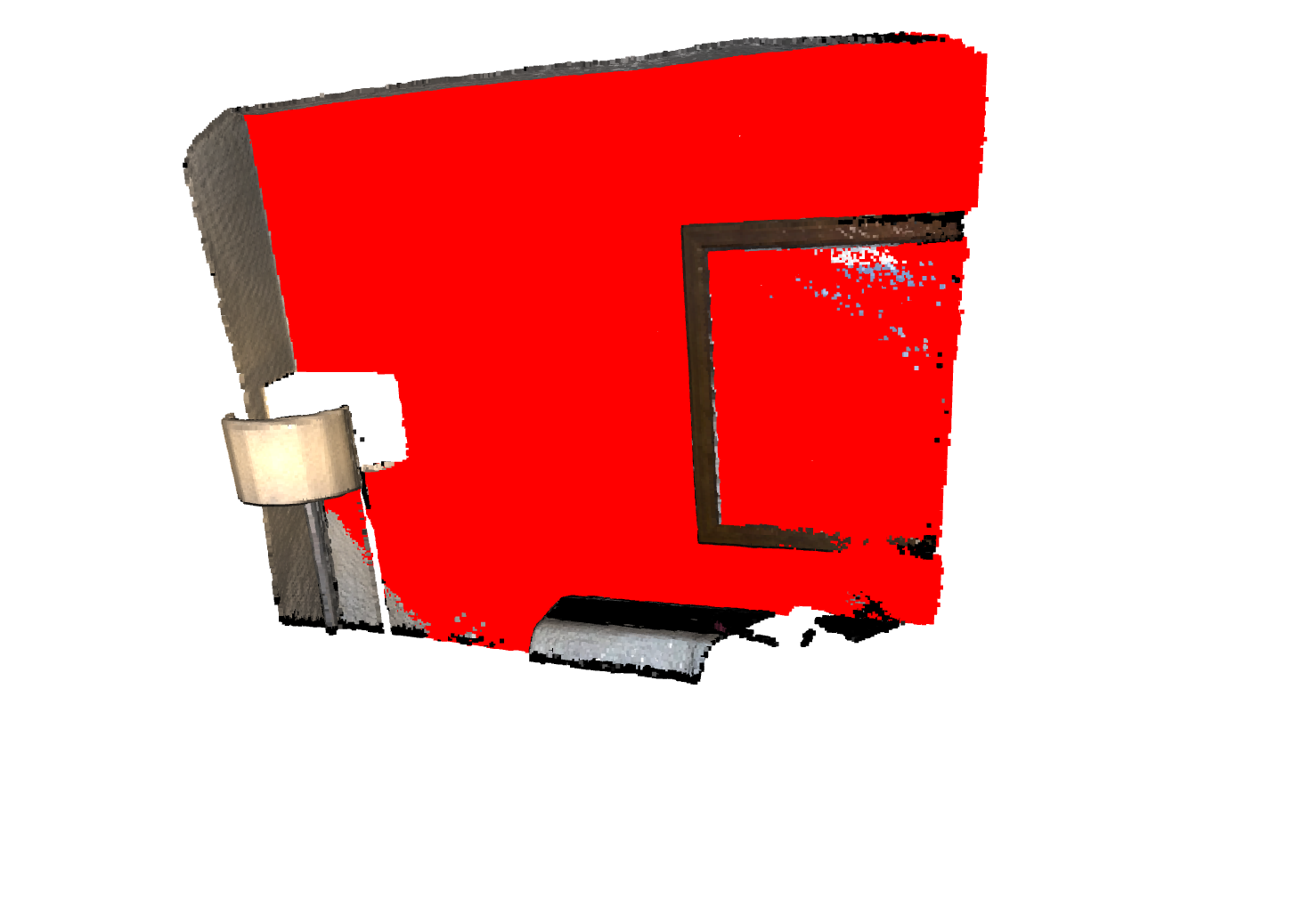

Below, you can see images of the point cloud pre and post RANSAC, with the red dots representing the largest plane.

The point cloud before finding the largest plane

The point cloud after finding the largest plane

Conclusion

In this post, we learned about RANSAC, easily one of the most popular outlier rejection schemes for many modern computer vision and robotics approaches. I hope that everything was clear, and if you need more clarity, please dig through my respository code, or feel free to email me. Cheers.